“The Demons and the Doubters, Or, The Gospel According to Breaking Bad”

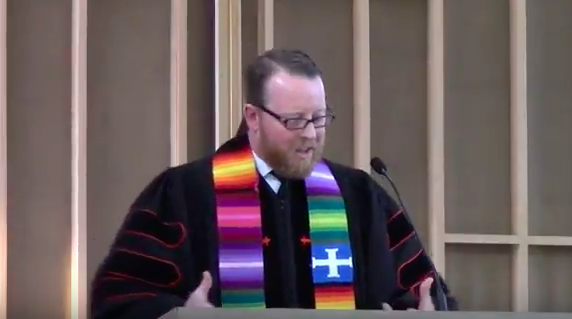

Rev. Dr. David A. Kaden

>>Open our eyes that we might see, wondrous things in your word. Amen.<<

Ten years ago in January of 2008, the first episode of Breaking Bad made its debut on AMC. Breaking Bad tells the story in five seasons and sixty-two episodes of Walter White – a middle-aged man with a PhD in chemistry, whose once promising career as a researcher ended, and he became an overqualified high school chemistry teacher with a teenage son suffering a disability, and a new baby on the way. To help his family make ends meet, Walter supplemented his income by working part-time at a car wash. Then he was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer, and he made the fateful decision to use his knowledge of chemistry to cook the illegal drug, methamphetamine. Walter’s decision was Machiavellian: the end justifies the means. He would cook meth in order to make $737,000 to pay off his mortgage, pay for his kids’ college, and set up a nest egg for his wife before he died. But entering the drug underworld transformed this once clean-cut chemistry teacher into a goateed and murderous drug kingpin.[1] His story is, as the band Nine Inch Nails sings, a “downward spiral.”

In its five seasons, Breaking Bad won sixteen Emmy Awards, two Peabody awards, and its lead actors and director all won prestigious awards. In all, the series won 110 industry awards in five years.[2] And when it became available on Netflix, viewers would watch strings of episodes in a row, which became what we now know of as “binge-watching”: one episode ends and ten seconds later the next begins, and you, the viewer, say to yourself, “I’ll just watch one more episode.” I have to confess that I binge-watched the last two seasons of Breaking Bad . And I have to confess further, that I binge-watched in August of 2014. And I did it as a distraction from studying for the oral examination of my PhD defense on September 5th of 2014. I passed despite the binge-watching.

An article in last week’s Vox magazine highlighted one episode of Breaking Bad in particular as pivotal for the whole series.[3] The title of the episode is “Fly,” which appeared in season three. In that episode, Walter White is the lead chemist in a meth superlab, and is having an existential crisis. All of his justifications for cooking meth are beginning to unravel. He has more than enough money to care for his family – by the end of the series he has tens of millions of dollars. And he’s coming to grips with the fact of who he really is: he has killed; he has lied; he has betrayed his family; he has no true friends; and the stories he tells himself to rationalize his actions are all lies. He could, in that moment, walk away. But instead he fixates on a fly. A fly is buzzing around his lab; and Walter views it as a contamination. He spends an entire night trying unsuccessfully to swat it: he slaps at it; he swings at it with a clipboard; he turns on the lab’s fans to suck it out; he throws his shoe at it; tries hitting it with a broom; he climbs a ladder to get it, and falls off. He fixates on the fly – the one thing he thinks he can control in a life that seems otherwise out of control. In their “unofficial companion to Breaking Bad ” titled Wanna Cook? , Ensley Guffey and Dale Koontz describe the “Fly” episode as Walter’s “long night of the soul,” “when he is no longer able to believe his own [lies], and a period of time when he desperately attempts to ignore this pain by obsessively focusing on [the fly] … . [But] no matter what Walt[er] tries, he cannot kill his fly, just as no matter what [he] tries, he cannot kill his conscience … .”[4] He cannot kill his demons.

Breaking Bad is full of demons. The demons that torment Walter’s conscience. The demons that manifest themselves in love of money and power, and in human pride. The demon of financial insecurity that drives a high school chemistry teacher to cook meth. The demon of the healthcare industry, and the bankruptcies it can create. The demon of addiction. Last Sunday’s New York Times had a front page article on addiction. It tells the story of Patrick Griffin, a man addicted to fentanyl and heroin, who overdosed four times in just six hours, each time revived by paramedics who gave him Narcan, an antidote to opioid overdoses. The New York Times followed Patrick and his family for a year, and the article provides a window into what addiction does to families. “Over the months,” says the article, the lives of Patrick and his family “played out in an almost constant state of emergency or dread, their days dictated by whether Patrick would shoot up or not. For an entire family, many of the arguments, the decisions, the plans came back to him and that single question. Even in the cheeriest moments, when Patrick was clean, everyone – including him – seemed to be bracing for the inevitable moment when he would turn back to drugs.” The website drugabuse.gov reports that more Americans died of overdoses in 2016 than died in the entire Vietnam War, whether from synthetic opioids, heroin, natural opioids, cocaine, or methamphetamine.[5]

We tend to classify the demonic as a spiritual force – a dark side of the force, to borrow a phrase from Star Wars . But there’s a material side. A physical, flesh-and-blood side. We might see the “demonic” at work in a tortured conscience, like that of Walter White, or in the contorted face of someone filled with racist or homophobic hate, or in someone so driven to succeed that they forget how to love. Maybe we see “demons” at work when a family is fractured and ground to dust because of poverty or addiction or mental illness. Maybe “demons” can be injected into arms or inhaled into lungs. Maybe our culture’s fetish with guns is a “demon.” Maybe some “demons” are invisible to us. Six years ago this past Wednesday, one of my close friends in graduate school stepped out onto his 21st floor balcony in Toronto and jumped to his death. He was just 29 years old. It was a crushing loss. I had been out to lunch with him only a few days before; we were laughing and chatting about our research. I’ll never know what demons he battled that night, or what demons he had been battling in the weeks and months that led up to that night. I pray his family has some answers. But the news of Nick’s death unleashed my own demons, my own self-doubt: How did I miss this? What’s the point of this rarefied education? Maybe I should just quit. Have I lost touch with the suffering of another human being, a close friend? It was one of those moments in my life, and there have been others, when I felt a visceral pull toward ministry – toward connecting more closely with human beings in their suffering and pain.

In the first of today’s gospel readings, Jesus encounters a possessed man. What’s so powerful to me about this story is not that Jesus teaches with authority or that he can cast out a demon. Exorcists and profound teachers were common in the ancient world; people filled with divine power were expected to teach well and even exorcise demons. No, what makes this story so powerful to me is its humanity. Mark introduces the possessed man by writing, “And there was in their synagogue, a man.” The man with the demons is introduced by Mark first as a human being. He’s just a person. He is not his demons; he is a man with an identity and a value apart from his demons. And actually, Mark paints this scene in an almost nonchalant, even comical, sort of way. Jesus enters the synagogue. And in the synagogue are the regulars, who attend weekly services, including the possessed man. I could imagine Mark introducing them by name: here’s Judah, here’s Simon, here’s Susanna, here’s the possessed man, here’s Joshua, here’s Esther, etc. etc. The possessed man is just part of the congregation. It’s only when Jesus shows up in the house of worship that chaos ensues. His teaching stirs souls, and creates uproar in the congregation. His presence causes the demons to quake and scream, because they know he’s come to cast them out. Maybe Mark is challenging us to ask the question: What would happen if Jesus showed up here on a Sunday morning?

But maybe this story is also challenging us to see past the demons and focus on the person – to smash the boxes we place people in, and just see the people; to erase the categories we use to label people, and just call them “people.” To see not the demons or the boxes or the categories, but the man sitting behind us; really see the woman on our left, or the teen or the child or the person in gender transition on our right; or the immigrant or the inked and pierced 20-something or the person whose skin looks different from ours sitting in front of us. To see them , and not their addiction or their state in life or their mental illness or their tortured conscience or their appearance. I think this is exactly what today’s second gospel reading is getting at. This story, like the exorcism story, takes place on a Sabbath in a Synagogue – on a Friday in a Mosque, on a Sunday in a church. Instead of a man with a demon, it’s a man with a withered hand, but Mark introduces him the same way: “And again Jesus entered a synagogue,” writes Mark, “and there was a man.” The man is not his disability; he’s a human being with an identity and a value apart from his withered hand. And Jesus sees him as such. Jesus is willing to smash through religious rigidity and tradition in order to treat the man as a human being. The religious authorities look on aghast at Jesus – some sects of ancient Judaism viewed healing on the Sabbath as a form of work, and thus a breach of God’s command to rest on the Sabbath. These authorities fixate on their tradition, on their boxes, on their categories – the things they think they can control, like Walter White and his fly. But Jesus doesn’t care about these traditions; he’s willing to break the rules and the laws if the rules and the laws blind us from seeing people as people. He ignores the tradition about Sabbath law; heals the man, and unleashes the demons that will ultimately put him on the cross. Mark concludes the story by saying, “immediately the authorities left, and discussed how they might destroy Jesus.”

The beauty of progressive Christianity is our emphasis on the person – on the person as a human being in spite of their demons. I believe we follow a progressive Christ, who treated every human he encountered – and this includes the Walter Whites of his day – as children of God. And this is so hard to accept, because there are real monsters in the world, real demoniacs – Larry Nassar-type-monsters, possessed in ways we can’t fully understand. But monsters possessed by demons whom we ultimately entrust to God – to a God who, as scripture says, has the power to make all things new. A God who can heal and restore victims. A God who can forgive and recreate in ways we simply can’t. But a God, enfleshed in a Christ, who pioneered a way to save us all: a way through our human-made categories and boxes and labels and Walter-White-type-flies; the way of the cross that crucifies all of that, and leads to eternal life, to God’s -type-of-life for us.

…There’s a Facebook video I saw recently that talks about boxes.[6] It takes place on a stage with about a dozen or so painted boxes on the stage floor. The narrator asks, “what happens when we stop putting people in boxes?” “It’s easy to put people in boxes,” says the narrator. And, as he speaks, people begin walking onto the stage. “There’s us and there’s them,” he continues. “The high earners, and those just getting by.” As he says this a group of well-dressed men and women gather in one box, and a group of people dressed casually gather in another. There are “those we trust,” says the narrator, and a group of medical professionals gather in a box. And there are “those we try to avoid,” he says, as a group of tattooed men dressed in baggy pants enter a box. The narrator continues: there are immigrants and “those who’ve always been here” – more people enter boxes. There are “the people from the countryside and those who’ve never seen a cow,” says the narrator, as more people enter boxes. “The religious and the self-confident,” he says. “There are those we share something with, and those we don’t share anything with.” More people step onto the stage and stand in boxes. A man on stage begins to speak: “Welcome,” he says to the people gathered in boxes. “I’m going to ask you some questions today. Some of them might be a bit personal, but I hope you will answer them honestly. Who in this room was the class clown?” Everyone on stage laughs, and several gather at the front of the stage. “Who are step-parents,” asks the man? A new group of people steps forward and congregates. “And then suddenly, there’s [only] us,” says the narrator. “All of us who love to dance,” he says as a new group gathers. “We who believe in life after death,” he says, and another group steps forward. “We who’ve seen UFOs,” he says, as another, albeit very small group, steps forward. “We who’ve been bullied,” he says, and “we who’ve bullied others” – new groups of people step forward. “We who are broken hearted.” “We who are madly in love.” “We who feel lonely.” More people step forward. The narrator continues, “we who are bisexual.” One person steps forward, and the crowd applauds. “We who have found the meaning of life” – more people step forward. “We who have saved lives.” “And then there’s all of us,” says the narrator. And everyone steps forward. “So maybe,” he concludes, “there’s more that brings us together than we think.” The clip ends with the people on stage greeting and hugging each other.

…The title of today’s sermon says “The Gospel According to Breaking Bad .” I don’t know if there’s any good news in that series. So many lives were destroyed by Walter White. But if there is a gospel to be found in Breaking Bad , maybe it’s delivered by way of question: Into what box do we put a person like Walter White? High School chemistry teacher? Father? Husband? Brother-in-law? Murderer? Meth cook? Liar? Monster? He’s all of these. But maybe Jesus teaches us in today’s gospel stories to focus on only one box. The same box that we find in that Facebook video. The box called “human being.” The box we all share in spite of our demons. Amen.

1 If you’re interested in the evolution of this protagonist: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8h-iAZBtNrs

2 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Breaking_Bad#Awards_and_nominations

3 https://www.vox.com/culture/2018/1/20/16910760/breaking-bad-10th-anniversary-birthday-structure

4 Ensley F. Guffey and K. Dale Koontz, Wanna Cook?: The Complete, Unofficial Companion to Breaking Bad (Toronto: ECW, 2014), 208.

5 https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

6 https://www.facebook.com/JayShettyIW/videos/1748936578754133/